Not at all coincidentally, I'm now reading the 1997 re-release edition of Lucy Lippard's Six Years (this copy courtesy of the PAFA library, but I will definitely be buying my very own copy because it is clearly a thing to which I should have forever-access). Needless to say, I have identified Lucy Lippard as a new personal hero. She rocks. So hard. Some excerpts from the intro that really clinched it:

"There has been a lot of bickering about what Conceptual art is/was; who began it; who did what when with it; what its goals, philosophy, and politics were and might have been. I was there, but I don't trust my memory. I don't trust anyone else's memory either. And I trust even less the authoritative overviews by those who were not there. So I'm going to quote myself a lot here, be cause I knew more about it then than I do now, despite the advantages of hindsight."

"The times were chaotic and so were our lives. We have each invented our own history, and they don't always mesh; but such messy compost is the source of all versions of the past"

"As I reconstitute the threads that drew me into the center of what came to be Conceptual art, I'll try to arm you with the necessary grain of salt, to provide a context, within the ferment of the times, for the personal prejudices and viewpoints that follow"

"In a de-commodified 'idea-art', some of us (or was it just me?) thought we had in our hands the weapon that would transform the art world into a democratic institution"

"Even in 1969, as we were imagining our heads off and, to some extent, out into the world, I suspected that 'the art world is probably going to be able to absorb conceptual art as another 'movement' and not pay too much attention to it. The art establishment depends so greatly on objects which can be bought and sold that I don't expect it to do much about an art that is opposed to the prevailing systems.' (This remains true today--art that is too specific, that names names, about politics, or place, or anything else, is not marketable until it is abstracted, generalized, defused.) By 1973, I was writing with some disillusion in the 'postface' of Six Years: 'Hopes that 'conceptual art' would be able to avoid the general commercialization, the destructively 'progressive' approach of modernism were for the most part unfounded. It seemed in 1969 that no one, not even a public greedy for novelty, would actually pay money, or much of it, for a xerox sheet referring to an event past or never directly perceived, a group of photographs documenting and ephemeral situation or condition, a project for work never to be completed, words spoken, but not recorded; it seemed that these artists would therefore be forcibly freed from the tyranny of a commodity status and market-orientation. Three years later, the major conceptualists are selling work for substantial sums here and in Europe; they are represented by (and still more unexpected--showing in) the world's most prestigious galleries. Clearly, whatever minor revolutions in communication have been achieved by the process of dematerializing the object, art, and artists, in a capitalist society remain luxuries"

"Perhaps most important, conceptualists indicated that the most exciting 'art' might still be buried in social energies not yet recognized as art. The process of extending the boundaries didn't stop with Conceptual art: These energies are still out there, waiting for artists to plug into them, potential fuel for the expansion of what 'art' can mean. The escape was temporary. Art was recaptured and sent back to its white cell, but parole is always a possibility"

"Everything, even art, exists in a political situation. I don't mean that art itself has to be seen in political terns or look political, but the way artists handle their art, where they make it, the chances they get to make it, how they are going to let it out, and to whom--it's all part of a life style and a political situation. It becomes a matter of artists' power, of artists achieving enough solidarity so that they aren't at the mercy of a society that doesn't understand what they are doing. I guess that's where the 'other culture' or alternative information network comes in--so we can have a choice of ways to live without dropping out"I mean...Can Lucy Lippard be my life coach please? Do you think she'd mind following me around saying obscenely articulate/ significant/ inspirational things to me for the rest of my life? No? Wellll I guess I'll just have to covet her writings then...

Another potential role model for life is Christine Kozlov. Yesterday, as I frantically copied the following affinity-inducing phrase out of Six Years into my sketchbook: "Kozlov showed an empty film reel, and made rejection itself her art form, conceptualizing pieces and then rejecting them, freeing herself from execution while remaining an artist," I mentally shoomed back to the moment I had in the Brooklyn Museum, scribbling the name CHRISTINE KOZLOV into my former sketchbook and drawing a huge box around it to affirm the dire importance of its addition, because though I'd heard or read her name before, I felt like I didn't know enough about her. "Oh yeah," I thought yesterday, firmly drawing yet another bold box around Kozlov's name because, clearly, the first hadn't been firm enough, "I meant to look her up." And now I had even more reason to--"freeing herself from execution while remaining an artist"??? Ummmmmmm, hell to the yes.

But a quick Googling has revealed that there is, like, ZERO information to be found on the Internet about Christine Kozlov! She doesn't even have a Wikipedia page! There are interviews in which people talk about her, and links to texts that feature her work or reference her as a part of the formative Conceptual times etc. but nothing remotely akin to a monograph or even a simple bio giving me basic details about the trajectory of her life and work. The part of me that wants to romanticize everything is tempted to turn this into a poetically appropriate turn of events: It is somehow fitting for Christine Kozlov to be as ephemeral as the work she made (or intentionally didn't make), for her to be digitally untraceable, for her un-documents to go relatively un-documented, for her existence to be a nebulous, evaporating thing. But then another part of me defiantly asserts, "NO! I need to know more about this artist with whom I am experiencing a recurring affinity, dammit!" The experience I'm having right now in 2013 seems to be similar to things she went through in the 1970s, according to what Joseph Kosuth had to say in a referential interview with him I managed to find:

"Christine and I were in art school together and had a personal relationship. She was also my best friend and we had a great dialogue. She had her particular kind of work which was very much her own and I think that we both learned a lot from each other as art students do. Then, things begun [sic] to happen and, as I was the ambitious male and a little more theoretically oriented - I was more of an activist while she was a quiet, introverted person - I was out fighting for this idea of art. At a certain moment she said something which filled me with tremendous feminist guilt (me as a feminist, not her); she said 'Well, you are doing it for both of us now' and I said: 'No, you cannot say that!' But it was quite horrible. I remember Lucy [Lippard] being in contact with her because at that point she really stopped; I tried also to encourage her and she eventually began to do work again but at a certain critical period she was quiet when she should not have been quiet, because we needed her. She was really the first woman in the Conceptual art context."So here's the thing: for the most part, I very much identify as a "more quiet, introverted person" (especially where me and my work are concerned) and I'm struggling to do work lately, and would therefore be completely ecstatic to be able to read Kozlov's own account of her experience considering she still managed to put some wildly fantastic things out into the world for quiet, introverted people like me to stumble across, empathize with, be inspired by. Clearly I need to do more than Google...Using Six Years as a launch point for further investigation is undoubtedly a solid place to start....

ALSO, Lee Lozano, who DOES have a wikipedia page, thank the Internet! This article in Frieze is really excellent, and has me convinced that Lozano is ridiculously appropriate for me obsession-wise. I think she more than Kozlov is probably a role model for life.

And now, Some of My Favorite Artworks Documented in Six Years (the book and the exhibition based on it):

- Bruce Nauman, Thighing 16-mm 8-10 min color film with sound (1967)

In which the artist manipulates the flesh of his thigh with his hands for a solid 10 minutes--weird, funny, mesmerizing to watch; made me think about how bizarre it is to have a body, what it means to have flesh, what are the properties of flesh/ a body, etc. It's very slow, which makes it even more hypnotic, and you get the feeling that you're watching him discover/ attempt to figure out this mass of meat that is his thigh for the first time--like a child discovering that it is an independent being with autonomy and motor skills, but he's not a child, which means that he is consciously inhabiting that frame of mind and performing the process of othering his own body to himself. But at the same time, it remains a simple, direct gesture. I also loved how the title is an invented verb that perfectly encapsulates the gesture itself--manipulating a noun into a gerund; manipulating one's thigh into malleable matter. Spoke to me on a personal level; resonated with my own concerns.

- Joseph Kosuth, Titled Series (Art as Idea as Idea) (1967) In which the artist proves that he is the cleverest fucker around, and I fully endorse it. Dictionary definitions for things are fascinating to me and frequently serve as a grounding point when I'm feeling confused abour a particular idea, word, concept, etc. So this is really good. Also, only one of these definitions has to do with actual output/ product--the rest are about skill and learning and the application of that skill and learning.

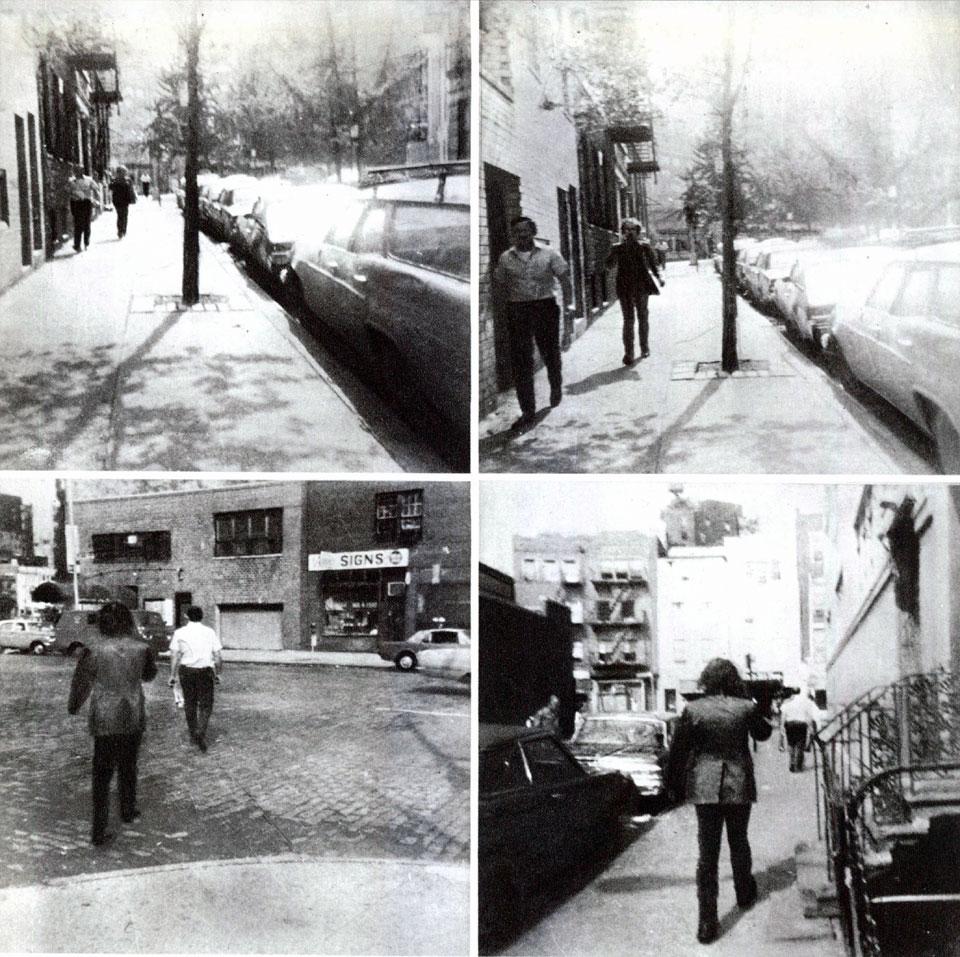

- Vito Acconci, Following Piece activity, 23 days, varying durations, NYC (1969)

In which the artist chose a random person each day to follow until they entered a private space. Immediate impulsive thought: "what a fucking creep!" Directly antecedent thought: "What a fucking genius!" A totally intuitive, though still systematic process/ gesture that really appeals to the narratively intrigued observer in me.

In which the artist chose a random person each day to follow until they entered a private space. Immediate impulsive thought: "what a fucking creep!" Directly antecedent thought: "What a fucking genius!" A totally intuitive, though still systematic process/ gesture that really appeals to the narratively intrigued observer in me. - Lee Lozano, Dialogue Piece (1969)

For which the artwork was the act of calling people up and inviting them over to her house to have a conversation, and the conversation that resulted, which was not recorded. OK, so LL's annotation in Six Years says: "Her art, it has been said, becomes the means by which to transform her life, and, by implication, the lives of others and of the planet itself." This is my approach to art too. This piece kind of reads as an attempt to reconcile being an introvert with knowing the importance of an active, intellectually stimulating social life. I sympathize. Also, I was doing a thing in this vein for a while last year, only kind of the opposite, in which I was frantically trying to document the conversations I was having with friends about an idea in order to incorporate their thoughts about the idea into the idea itself [the idea was for there to be an exhibition of the documentation of the conceptualizing of the exhibition that just keeps growing and being added to by the attendees of the exhibition, who can contribute their thoughts and suggestions, which will then be incorporated into the exhibition. I know.]. General Strike Piece (started 1969) and Masturbation Investigation (1969) are also extremely badass. I like that her pieces' only evidence are these handwritten pages documenting her intentions. The lived experience is the art, which cannot be translated into a visual or an object, so the original idea, the impetus of it, is what survives.

For which the artwork was the act of calling people up and inviting them over to her house to have a conversation, and the conversation that resulted, which was not recorded. OK, so LL's annotation in Six Years says: "Her art, it has been said, becomes the means by which to transform her life, and, by implication, the lives of others and of the planet itself." This is my approach to art too. This piece kind of reads as an attempt to reconcile being an introvert with knowing the importance of an active, intellectually stimulating social life. I sympathize. Also, I was doing a thing in this vein for a while last year, only kind of the opposite, in which I was frantically trying to document the conversations I was having with friends about an idea in order to incorporate their thoughts about the idea into the idea itself [the idea was for there to be an exhibition of the documentation of the conceptualizing of the exhibition that just keeps growing and being added to by the attendees of the exhibition, who can contribute their thoughts and suggestions, which will then be incorporated into the exhibition. I know.]. General Strike Piece (started 1969) and Masturbation Investigation (1969) are also extremely badass. I like that her pieces' only evidence are these handwritten pages documenting her intentions. The lived experience is the art, which cannot be translated into a visual or an object, so the original idea, the impetus of it, is what survives. - Dennis Oppenheim, Arm & Wire 16-mm film by Bob Fiore (1969)

In which the artist "repeatedly rolled the underside of his right arm over some wires". The wires leave imprinted marks in his skin, records of the contact between his body and the material. Arm and Asphalt (1969), Reading Position for Second Degree Burn (1970), and Material Interchange (1970) are other products of the thematic investigation of the body as marked recipient of the effects of an interaction with external forces/ materials. Resonated for me because of the emphasis on mark-making as a physical gesture/ as the remnant of a physical interaction (thinking about lipstick/the kiss)

- Marjorie Strider, Street Work (1969) Street Works I (March 15): 30 empty picture frames were hung in the area, to create instant paintings and to call the attention of passers-by to their environment. Street Works II (April 18): Same work, different area. In both of these works, most of the frames were taken home by people on the streets. Street Works III (May 25): A large felt banner (about 10 feet long) on which was lettered the words PICTURE FRAME, was hung in the area. Street Works IV (Sponsored by the Architectural League of New York, October): A 10' x 15' picture was placed in front of the entrance to the Architectural League, forcing people to walk through the picture plane. Street Works V (December 21): Taped frames were placed on the sidewalk, creating more picture spaces for people to walk through. Reminds me of Lorraine O'Grady's Art Is... (1983), which was among my favorites in the This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s exhibition at ICA Boston this past winter. Both involve the idea of framing life as the subject of art, but the fundamental difference in the execution is that Strider leaves the frames to do the compositional work, while O'Grady physically holds the frame, and is involved in the lived action being framed. I think I prefer O'Grady's for that reason--she is not an absent framer of compositions to be found, experienced, interacted with by others; she is a present participant, engaging with the people who comprise the content of the framed compositions. O'Grady's piece feels more empowering in that way--she is expressly telling people that their lives, their experiences are significant enough to be framed and documented, while simultaneously critiquing the history of art's lack of consideration and inclusion of those people and experiences. Strider's feels like an intellectual stepping stone toward O'Grady's more sociopolitically charged execution. But I guess that can be boiled down to the difference in the climates of the late-60s/ early-70s and the 80s.

- James Collins, Introduction Piece No. 5 (1970) (I couldn't find a paste-able image, but you can look at the document in Six Years here) For which the artist introduced strangers to each other and then had them sign a document verifying that the introduction had been made, the date, time, location and signature of both participants, as well as a picture. Another incarnation of the idea that human interaction/ connection/ exchange is art.

- Bas Jan Ader, Fall 1 (1970) Which is footage of the artist intentionally falling off the roof of a house. Fall 2, filmed in Amsterdam, shows the artist intentionally riding his bike into the river. Another piece of Ader's I really like, and which is featured in the book, is I'm Too Sad To Tell You (1971), in which he cries in front of the camera. I like how Ader's work highlights the trickiness of performance: he's really falling, but it's not a "genuine" fall because it's not an accident; he's really crying, but it's a self-aware, performed cry because he set up the equipment and knows the camera is recording it. How "authentic" can you be when you're framing/ composing the expression? I think about/ experience this tension a lot.

- Christing Kozlov, Information: No Theory (1970)

2. The recorder will be set at record. All the sounds audible in the room will be recorded.3. The nature of the loop tape necessitates that new information erases old information. The "life" of the information, that is, the time it takes for the information to go from "new" to "old" is the time it takes the tape to make one complete cycle.4. Proof of the existence of the information does in fact not exist in actuality, but is based on probability.I love everything about this.